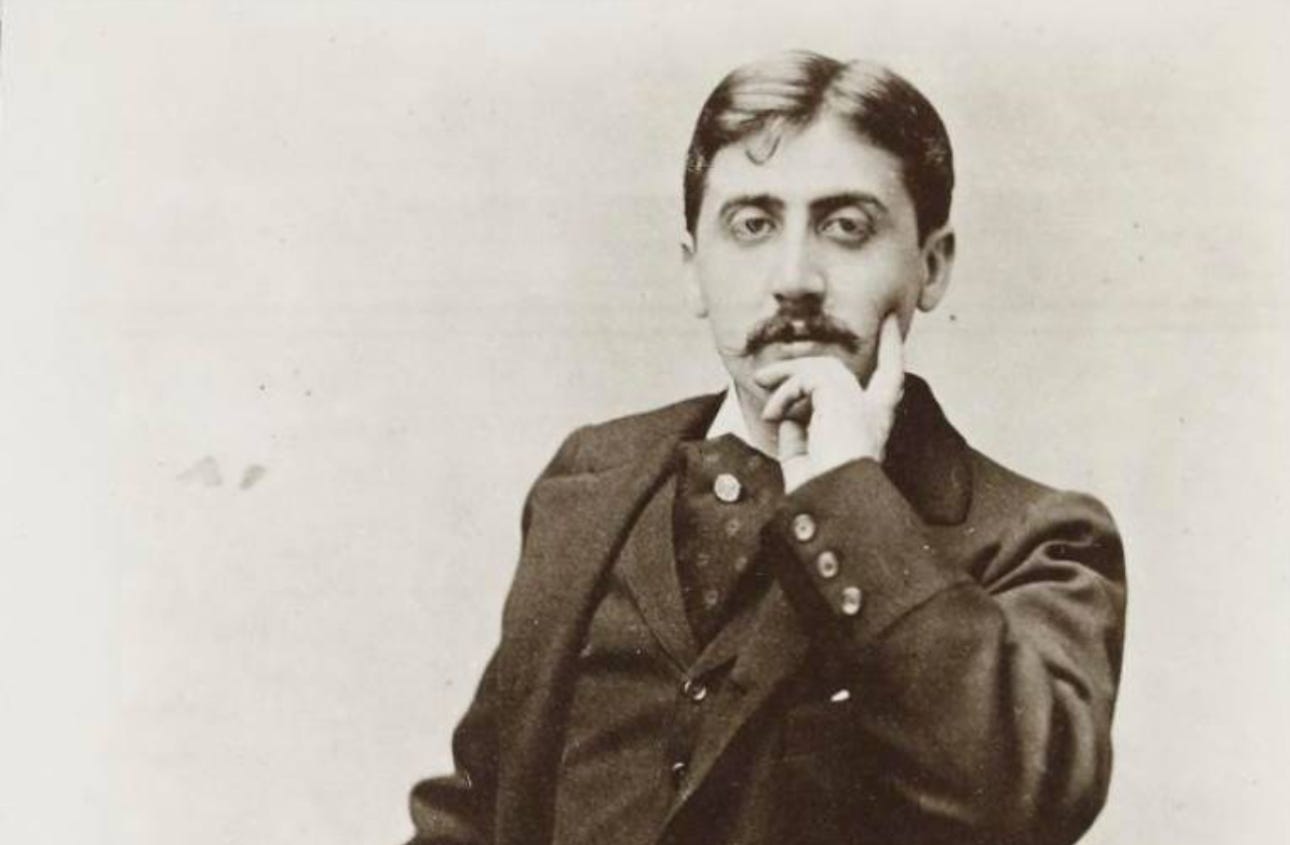

Proust on the miracle of reading

“In reality, every reader is, while reading, the reader of his own self.”

Proust once characterized the act of reading as “that fruitful miracle of a communication in the midst of solitude.” It’s a beautiful way of saying that the reader establishes a connection with the text, even though he is by himself. In this sense reading is both a solitary act as a well as a vehicle for empathy and understanding.

In a memorable passage in Volume One of “In Search of Lost Time”, Proust describes his protagonist going for a long walk after sitting inside reading for most of the day. He writes:

“My walks that autumn were all the more pleasant because I took them after long hours spent over a book. When I was tired from reading all morning in the parlor, throwing my plaid over my shoulders I would go out: my body, which had had to keep still for so long, but which had accumulated, as it sat, a reserve of animation and speed, now needed, like a top that has been released, to expend them in all directions.”

It’s a seemingly simple scene in which the young narrator describes going for a walk after reading a book all day. He compares himself to a spinning top, his mind and body full of energy needing to be released. And when he goes outside he wanders restlessly, without aim or goal other than to rid himself of this accumulated tension.

In the context of the book it’s worth noting that the young boy has recently lost his aunt Leonie, and he’s not quite sure how to feel about it. He’s sad, but also a bit unsure how to express himself. He’s seemingly indifferent, and yet secretly scorns the maid Francoise, who takes her mourning much more seriously than he does.

But it’s also an important turning point in the book, as it precipitates a scene in which the young narrator discovers that our inner worlds aren’t necessarily shared with others. The boy realizes this during a cathartic moment in his walk - he is leaning over a pond watching his face distort in the reflection- when he notices a man walking by completely immersed in his own thoughts. This leads to a rumination in which Proust writes that “the same emotions do not arise simultaneously, in a pre-established order, in all men.” Or, to put it in contemporary terms, the young narrator becomes self-aware and realizes that other people don’t necessarily “match his energy.”

It’s a simple, but defining insight: just because you are feeling one way doesn’t necessarily mean that other people are in the same headspace. You might be ready to chat when they just want to be left alone; and vice versa, they might want your attention when you’re busy trying to do something else. It’s a moment of recognition and self-awareness that leads the young narrator to an important discovery: we can’t see the world through somebody else’s eyes, but we can try to imagine it nonetheless. One way to do so is to read a book. And this (not quite coincidentally) is an insight that could only have occurred to the boy while he was outside, i.e. NOT reading a book. Or, to put it in Lacanian terms, the crucial insight is that reality itself is structured like a fiction.

Later, in a lengthy passage Proust theorizes on the nature of the novel as essentially dialectical. As he puts it: “The novelist’s happy discovery was to have the idea of replacing these parts, impenetrable to the soul, by an equal quantity of immaterial parts, that is to say, parts which our soul can assimilate. What does it matter thenceforth if the actions, and the emotions, of this new order of creatures seem to us true, since we have made them ours, since it is within us that they occur, that they hold within their control, as we feverishly turn the pages of the book, the rapidity of our breathing and the intensity of our gaze.”

It’s a characteristically Proustian way of saying that when we read we allow ideas and images of other people to enter into our heads, and in so doing they become a part of us. But we also create a version of them that isn’t real. This means that reality is itself a kind of symbolic fiction, in which we are constantly filling in the gaps. And since we cannot truly know what goes on in other peoples heads, or whether they experience the world the same way we do, we have to resort to the only reliable way we know how to overcome this gap: reading books.

Or to put it differently, we read not only to learn about others, but also so as to better know ourselves. It’s an inherently “solitary” act in which nevertheless a miraculous communication takes place. A communication which Proust deemed miraculous in the strictest sense of the word: namely an “object of wonder” (miraculum). For what could be more wonderful, and full of wonder, than that we are both uniquely ourselves and yet so very much alike? Consciousness, therefore, is both a mystery and a miracle: which means we read to know ourselves in and through the written words of others. And perhaps this is what it means to have and share human consciousness. We read to know we are not alone. Or, to quote another memorable line from Proust:

“In reality, every reader is, while reading, the reader of his own self.”

Julian

Thank you for reading my newsletter. To learn more, upgrade to a paid subscription by clicking below.

I have been reading since I was three. Not a prodigy, but my mother was a teacher & we all read at the table during meals. Did we also chat? I presume so, but books were The Thing & they have continued to make my hardest times bearable, best times illuminated, solitude desirable — as Proust notes. And provided me with a marvellous vocation/career from 1972 to present day.

I can now read (words or faces) with my left eye only. That leaves me vulnerable. Thank heaven though it is the left…or I would be seriously unbalanced.

Any hymn to reading is one where I’m glad to sing along.

The hymn below is no exception. What fun to discover it. 📚📚📚📚👏👏🔔

This is so very true: “In reality, every reader is, while reading, the reader of his own self.”

Isn't it fascinating to realize then how many interpretations a single book can have—each time a reader picks it up? And then to imagine the same for every book ever written?

That tiny mind exercise alone could restore your faith in humanity.

Thank you for provoking it. ❤️