Pessoa on Despair

"We don’t adapt, because healthy people cannot adopt to a sick milieu, and since we don’t adapt, it is we who are sick.”

One of the most powerful meditations on alienation comes from the writer Fernando Pessoa. In this passage he reflects on what it feels like when everything you cared about seems to be fading away, and you become unwilling to adapt to a world that seems to have gone insane.

“Only now can we fully understand what Voltaire meant when he said that, if there’s life on other planets, then the Earth is the Universe’s insane asylum, whether or not the other planets are inhabited. Our life has lost all sense of what is normal, and where there’s health, it’s just a remission of our illness. (…) We don’t adapt, because healthy people cannot adapt to a sick milieu, and since we don’t adapt, it is we who are sick.”

It’s an apt way of expressing the paradox that to be happy and care-free in a messed up world is itself a kind of insanity. Here Pessoa adds a beautifully Hegelian twist. Yes, we should accept that we feel despair, but we should not accept that we accept it. As he puts it, “An attitude of indifference is a decadent attitude.”

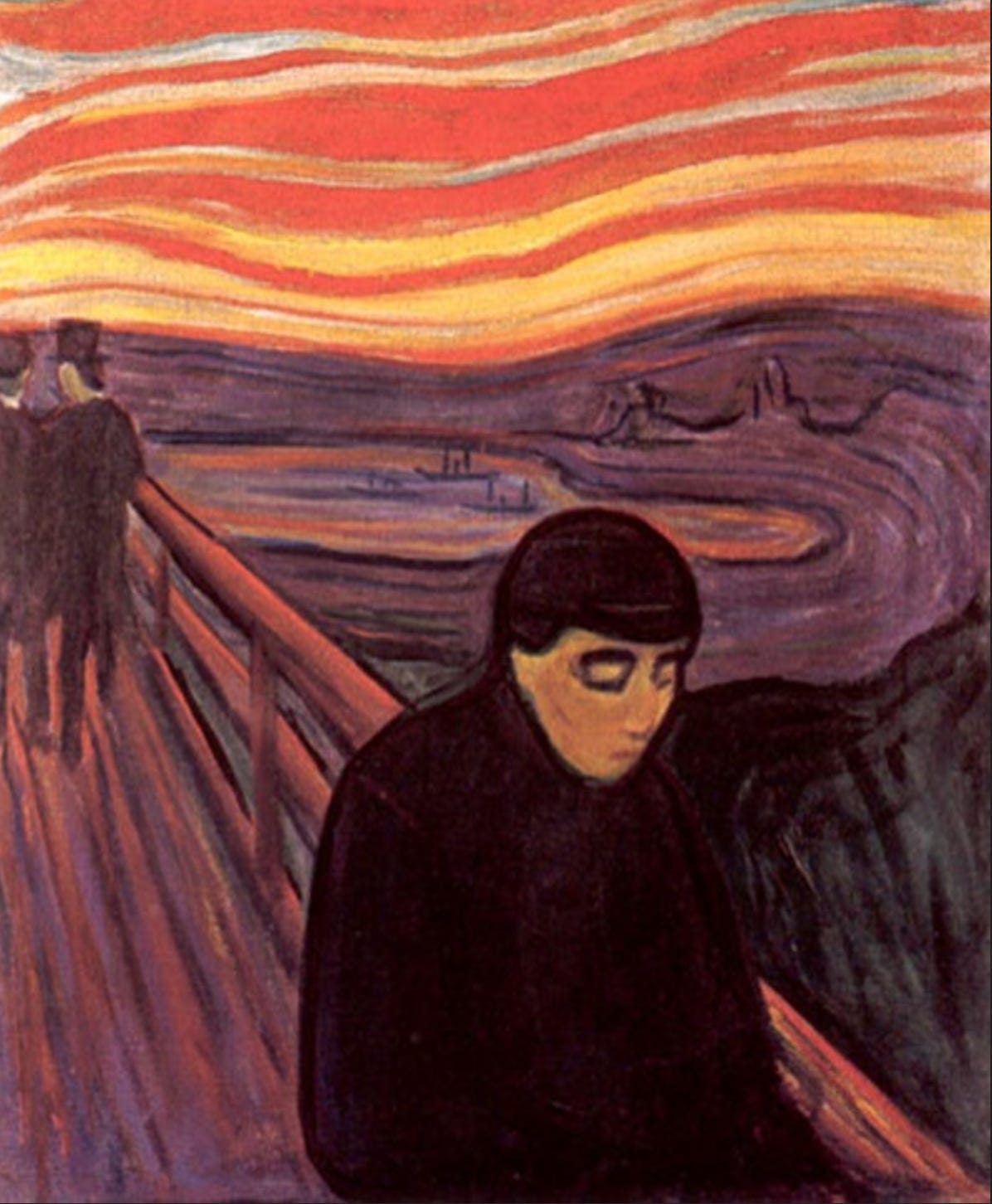

In this painting by Edvard Munch, titled “Despair” (1894), we see the silent anguish of such suffering, a sense of slowly fading away.

We see a man walking alone across a bridge. It’s the same scene as the famous ‘Scream’ painting, and yet it depicts a very different energy. This is not the agony of total despair, but rather a quiet, more subdued kind of pain. The anguish of doubt and inner turmoil, not the release of energy that comes with desperation.

Here we can see the difference between the German words Zweifel (doubt) and Verzweiflung (Despair). The first is less dramatic, but no less painful. The subject’s suffering is increased because he must bear it alone. Whereas despair implies the dissolution of the subject as such. Munch depicts the silent agony of internalized anguish, what Freud might have called an Unbehagen in der Kultur.

Both Pessoa and Munch believed that the ‘inability to adapt’ was only a reasonable response to the changing world they inhabited. Like Nietzsche, who characterized ‘healthy’ living as itself an illness (“what is today called healthy represents a lower level than that which under favorable conditions would be healthy.”), they believed that to sublimate this form of unease was the only way to get back to a position of truth.

The underlying ‘message’ therefore, i.e. the implicit imperative in their work, is that we must continue to write, think, and create for ourselves and for each other. But that we must do so in a way that does not simply turn away from our anguish, so as to find a new language for expressing it. Which is to say, rather than just succumbing to despair, we must make it our theme. And in so doing, seek to overcome it.

We live in extraordinary times. And there are many different shades of despair. And yet we must keep on doing the best we can. Each of us, in our own way, must continue doing the things that matter most, without succumbing to the dual temptations of indifference or cynicism. Yes, we should accept that we feel despair. But we should not accept that we accept it. We must keep on writing, teaching, reading, creating. For ourselves, and for each other. As Kafka put it (apologies for repeating this line, but I am so very fond of it), “everyone has their own way of escaping the underworld. Mine is by writing.”

Apologies, towards the end I use the verb “disavow”, when it should have been “sublimate”.

❤️🙌🥹